The English High School of Istanbul of the 1970’s was a remnant of its glorious past as was the mother country it represented. It clung on to old traditions, at least on the surface. Beset by endless financial difficulties, the school seemed to hold together by a thread, and indeed disintegrated several years after my graduation in 1974. But in the late 1960’s, when I entered it, these traditions, not yet eroded by financial cutbacks were still very much alive.

They included a proper uniform befitting the fortunate children of the British upper class, and an extensive sports program practiced in a large field the school owned on the edge of town, which featured not only various common ball sports like soccer, but also uniquely British ones like rugby and cross-country. It also included our school’s own version of the Olympics held every spring, known as Field Day. All children belonged to one of four teams that divided the student body, ostensibly for sports, but in practical reality into social cliques, or organized gangs. These were named after famous English forests, Sherwood, Arden, Charnwood and Dean. We all rooted for our own, and tended to be more friendly with our fellow gang members. The ultimate competition between these teams occurred in Field Day.

P.E. class was a big production in those early days for we had to be bussed to the facilities from the school’s main building in a cramped and crowded upscale neighborhood called Nishantash. We then had to change in the locker rooms, engage in the class, return to our clothes with no showers (hygiene was not that important then), and be bussed back. Thus we spent more continuous time with our gym teacher than others who came and went in hourly teaching sessions.

The teacher staff at EHS was a curious assortment of British and American outcasts melded together with mature, serious and dedicated Turks. The latter mostly taught the necessary Turkish curriculum, and the former provided the much coveted English, so rare and so much in demand in those days. These English speaking teachers, the element that made EHS so special and distinctive, were in practical reality a bunch of misfits who, unsuccessful in their own society, had come to exile in exotic Istanbul. We had flaming homosexuals, in those days taboo figures subjected to clownish ridicule; we had alcoholics, we had an assortment of English eccentrics. We even had a British spy who happened to be our Headmaster nonetheless. This crowd routinely turned over every two or three years, providing the colorful cast with yet new, fresh faces. By contrast the solid foundation of the Turkish faculty rarely turned over, and thus were the anchor that kept the school grounded. Curiously many of the Turks did not speak English, and the two teacher bodies co-existed with cursory knowledge of each other.

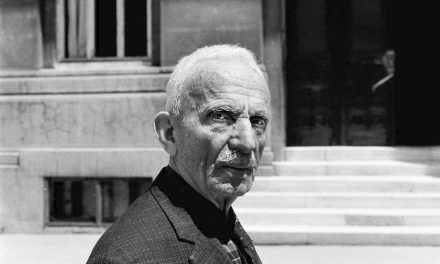

Sometime in the late 1960’s a new character entered this peculiar mélange who was to stand above them all, and become the most memorable teacher of any who came in contact with him. He came to represent the Dickensian element of the British tradition at its most awful, in retrospect yet another necessity of a fully rounded English education. His name was Mr. Wilcox, and he hailed from Australia, a source that could not have been more dramatically appropriate, for Mr. Wilcox was undoubtedly a descendant of the worst element of that primordial gene pool which created this country. He was a P.E. teacher.

Tall, stocky and with the permanently red cheeks of a chronic alcoholic, Mr. Wilcox looked more like a displaced old sailor out of uniform than a gym teacher. He had a loud, booming, scary voice, with a unique Australian accent giving his delivery a higher touch of terror. Verbal and physical abuse was his specialty, and this he did with the characteristic skill of a well practiced craftsman. No one escaped Mr. Wilcox’s screams and swears not to mention the stinging pain of his slaps. It seemed that no kid in that school was good enough for Mr. Wilcox. He sniffed out their faults like a wild animal looking for prey, and when he locked in, began his work to snuff them out, forcefully. Us kids were too outgoing or too shy, too athletic for our own good or deconditioned slobs, we were never disciplined enough for his pleasure. There was always a pretext to berate us in every P.E. class, including during the bus ride back and forth, his abuse rising and falling with a Beethovenian rhythmic drive, a few swears here and there with spit flying out of his mouth, a few hits and slaps when it rose to a crescendo. Instantly upon his arrival in Istanbul, Mr. Wilcox became the scariest element of our young lives.

At first I felt particularly vulnerable to his wrath because when it came to athletics I had no talent whatsoever. Later I was to find out otherwise. Curiously the first lesson I learned from Mr. Wilcox turned out to be about English vocabulary rather than sports. When still new to the school he did not know which kids possessed athletic talent. In one of his earliest classes during a dreary, drizzly winter day, out in that field on the edge of town, he picked me to play center forward in a soccer game. The whole class was divided into two teams and he assigned positions to each kid. For those unfamiliar with the game, that center-forward position is the most critical in soccer, usually reserved for exceptionally talented strikers with unique goal producing capacity. Not only was I totally ill suited for the position but I did not even know the first thing about it: how to engage the ball in the game at the start, a task given to the center forward. I kicked the ball this way and that, and each time I violated some soccer rule I did not even know, drawing loud whistles from Mr. Wilcox who was acting as the main referee. After several false starts I could see the rising frustration in his face. He came to me and loudly told me to get out of the position and become a linesman, an accessory referee watching the sideline for outed balls and fouls. He handed me a red flag, the only tool for the job and sent me out.

As you might have guessed, I was even less suited for this job, for I knew precious little about the nuances of soccer rules. While relieved to get away from the soccer ball, and at a safe distance from Mr. Wilcox’s menacing presence, I fearfully watched the game and prayed that the ball didn’t come near my side of the line. Naturally it did. Many times. And as Mr. Wilcox, the main referee looked at me for guidance in making line calls, I raised my flag and pointed it in this and that direction as I saw linesmen do in professional soccer games. The awkward and random movements of my flag made no sense, and soon Mr. Wilcox discovered my ineptitude. He ran over to me and screamed, “YOU LUNATIC!”, as he ejected me from the game and sent me to the locker room. Walking out of that field with my head held low, ashamed and humiliated, I was nonetheless relieved at escaping the situation with only a single exclamation from my tormentor.

My relief was enhanced by my ignorance of the word. “Lunatic?”. I pondered. I knew “luna” referred to the moon. What did the moon, or being from the moon have to do with soccer, and my inability to play it? The question gnawed at me for the rest of that day until I returned home and to a large, lofty English-Turkish dictionary my father kept. I discovered that it meant “crazy”, and I never forgot this new word. To this day, on those few occasions that I encounter this rarely used word, an image of that drizzly day in Istanbul flashes in my mind, with me on the line, my flag down by my hips exhausted by incompetence, as Mr. Wilcox runs towards me, my terror rising within, and my subsequent relief. “Lunatic” is a kind word.

After this episode I kept a low profile, and discovered that Mr. Wilcox actually had little interest in kids with no talent. He focused on the talented ones with spirit, ones who had courage to defy him, or those who simply screwed up repeatedly because this was their nature. I spent a lot of time in defender positions in soccer where the ball rarely came near me, I quietly obeyed all his commands, and watched with much relief as he unleashed his fearful wrath at others. I watched him slap my classmates, kick them, thrown them on the ground, throw balls or other objects at them, make them engage in punishing excercises and more. I successfully evaded these outbursts and quietly became proud of this accomplishment. Still, Mr. Wilcox could inflict humiliation of indescribable pain without even knowing he was doing it, and this I experienced once in an unforgettable episode from my youth. It occurred in the only other sports venue the school possessed: an indoor gym in the main school house in Nishantash.

This gym was also used as a theater and it had a stage. Here we played basketball and volleyball, engaged in P.E. class in inclement weather, and also used it for general assembly and school plays. The facility was small and had no room for viewer stands on the sides. Thus, the only way to view varsity competitions was from the stage. There was only one entrance to the facility on the side of the field opposite the stage. In other words, once a game began, if you were an audience member, you could not leave without walking through the playing field. Thus no audience member was allowed to leave the stage unless there was a break in the game, like half-time.

A few years after Mr. Wilcox’s arrival I was officially a teenager, and at age 13, I assumed the typical teenage attitude of not wanting to be seen around with my parents. One day, I attended a particularly critical after school varsity basketball game as an audience member. It was a hotly contested game between two accomplished “gang-teams” named after those forests. It seemed like the entire student body was cramped on to that stage for the occasion. As it so happened, my mother needed to run some after school errand with me and I forgot to tell her about this game. So she came to school looking for me and could not find me. That’s when, right in the middle of the basketball action the door of the gym opened there appeared my mother’s face peering in.

Mr. Wilcox, the usual referee for all games, saw the door open and immediately blew a loud, irritated whistle. The game, fast in momentum until then, came to a sudden stop. Mortified, I tried to hide within the large crowd on stage. Then I realized that it was not just my mother but also her sister, my aunt Victoria and Victoria’s two female friends Firdevs Hanim and Hayriye Hanim who were also with her. All of a sudden there were four old ladies looking for me, Mr. Mama’s boy. They spoke no English. So one of the players translated their quest to Mr. Wilcox. He was polite with them, irate as he was at the interruption. Once he figured out what they wanted he turned towards the audience at the stage and screamed, “does anyone have a mommy here?”. He placed a special emphasis on “mommy”, mockingly making it sound like, “maaaaaaammmmy”. Dead silence followed, the whole gym wondering who this pansie mama’s boy would turn out to be. As the seconds advanced I came to the horrified realization that if someone did not appear soon the game would be indefinitely on hold, with unknown dire consequences. And so I rose, slowly, in the stands and moved forward on the stage.

My mother displayed an expression of delight on her face as soon as she recognized me. Mr. Wilcox, standing right next to her bore a different expression. I walked across the basketball field towards that door, the slowest and most humiliating walk of my life, feeling the disdainful eyes of the entire student body on me, and of course those of Mr. Wilcox spreading fire with his gaze locked on my forward lurched body, head hung low. My nearly eternal, slow motion promenade ended in the arms of not one but four “mooommmmies” as they cheerfully greeted me in front of everyone, providing a suitable climax to my complete humiliation. The door closed and the whistle went off. My mother wondered why I was so cross with her for the rest of that day.

In the Istanbul of my childhood physical and verbal abuse of children was not only allowed but it was actually encouraged if this were the only means to achieve discipline, a major ingredient of this historically militaristic nation. Thus it was not unusual for various teachers to occasionally slap us, or administer other forms of physical punishment. One of the bedrock Turkish teachers Mr. Deleon, actually Turkish-Jewish, who taught math, had a much dreaded stick with which he kept his flock in line. It actually had a name, “kizilcik” which means cranberry, for that was the color it left in the bottoms of miscreants it regularly connected with. Mr. DeLeon had a unique trajectory he had perfected over the years, tangential to the round curve of bent bottoms, which stung worse than a regular direct hit. Thus we were all accustomed to a certain level of such punishment. Mr. Wilcox however, single handedly brought this level to a hitherto unimaginable stratospheric level. The terror he unleashed was so widespread and complete that he unintendedly, and unofficially became a one-man security force. Any yard fight, or other above average misbehavior was brought to his attention and he swiftly dealt with it. His tenure brought superficial calm to the school, as public displays of misconduct went underground and our youthful mischief was re-aimed to areas harder for him to detect, mainly the mild mannered and non-intimidating Turkish teachers.

A couple of years after he arrived we were all amazed to discover that there was a Mrs. Wilcox, and she was also a teacher. She appeared one day as our new English teacher. She was tall, thin, and rather dry, with a uniquely English sense of propriety and no humor whatsoever. She was a dedicated and effective teacher however, and did a good job of educating us. Naturally no-one ever dared to misbehave in any way in her classes. Discipline came easily for Mrs. Wilcox for wherever she went, the invisible shadow of her fearsome husband accompanied her. We all wondered how fearful she herself was of her husband and whether he treated her the same way as us. She never displayed bruises, shiners or other evidence of domestic abuse, but we knew there had to be some. We wondered how this prim and proper erudite woman could live with a wild brute like Wilcox.

On one unique occasion Mr. Wilcox acted as a substitute teacher for his wife, for reasons I no longer remember. Considering that his knowledge of English vocabulary was mainly restricted to pub-speak and slang, and he most likely had about as much literary exposure as a cave-man, we all wondered what on earth he would teach us that day. He spent a memorable hour with us, standing at the head of the class with regular clothes, looking even more brutish than he did in his gym outfit, with no whistle on his chest and us all seated, inactive and attentive. He gave us a lecture on the evils of a welfare state. He used phrases like “on the dole”, which we did not understand. Turkey in those times was definitely not a welfare state. Everyone was on their own, or at the mercy of their extended families. No one looked for the government to solve the ills of the socially weak. Thus the lecture was irrelevant even if we were delivered to older students better versed in politics. But to our young minds that cared precious little about such matters his lecture was essentially Chinese. Still we observed him pace back and forth the front of the class, amazed at his emotional sermon, delivered without the usual screams, yells, threats and beatings. It was the only hour I ever spent with Mr. Wilcox where he did not erupt.

As the years went by I took pride in never having received a physical blow from Mr. Wilcox. This was mainly due to my ineptitude that kept his attention away from me. My luck however was soon to run out as I discovered with surprise and dismay, in an episode that exploded out of nowhere. We were in that same indoor gym where I had been humiliated by the four mommies, engaged in an indoor P.E. class. The subject was push ups. I discovered that day that there were kids around who were even more inept than me, unable to engage properly in this rather rudimentary exercise. We were all lined up in front of Mr. Wilcox who called each kid out one by one and demanded they display their push-up skills. Most did this with ease, and the class proceeded in a rather boring monotone. That is until this one hapless kid initiated a most comic display of deranged push-up variants. He laid prone with his chest and stomach touching the ground as though he was sun tanning and then rose, with great effort, only to fall back into the suntan position. This he did with the rhythm of a car experiencing extreme engine knock. It did not take long for Mr. Wilcox to fire up his explosive anger. He screamed at the kid to do it right, and when he couldn’t, came over and picked him up by the back of his T-shirt. He then proceeded to repeatedly lift and drop the boy in what amounted to externally forced push ups. The boy flailed like a rag doll his limbs flying every which direction as he rose in the air, and fell down like a sack of potatoes, if you can imagine one with terror on its face.

It was funniest thing we had seen in a long time. The entire line of boys erupted into laughter. If there was one act Mr. Wilcox never wished to perform it was that of a comedian. Our laughter raised his ire even further. He dropped the boy fast and hard, turned towards us with one of his reddest and fiercest faces and screamed, “SHUT UP!”. The group instantly silenced, well accustomed as we were to these commands by now. But not all. I just could not stop laughing. My laughter was not meant to be in a mean spirit; God knows I knew the humiliation this boy felt lying prone and limp on the ground afraid to move a muscle. I felt as sorry for him as I did for all Wilcox’s victims. But the situation was plain old funny. I just could not get myself to stop laughing. That’s when Mr. Wilcox’s large hand found my cheek, in a stunningly powerful slap. I was laughing so hard the instant before that I didn’t even see him approach. He came quietly at me like a wild cat lurching at his prey. The blow sent my face flying the other way, and brought instant stars to my vision as my eyes filled with tears. Now everyone was silent, myself included. Afterwards, I licked my wounds and cursed myself for breaking that long spell of good luck in a moment of comic weakness.

Mr. Wilcox consistently held a reign of terror against the younger boys in lower classes. But the older grades, already thick with teenage rebellion, and possessed with considerable resources of anger and violence, provided a few courageous souls to butt heads with him. Occasionally this happened within the formal setting of gym class. Mr. Wilcox attempted to teach us the rough and tumble sport of rugby, and at times he actually played as a team member rather than his usual role of referee. Now he was “free game”; all the kids could take a pot shot at him since hitting the opponent any possible way was the essence of this game. There were no fouls. I recall these dirty games played in muddy fields, Mr. Wilcox running with the ball and several kids locked on different parts of his body dragging along, some hitting him, some kicking. Everyone had a great time on these occasions when we could hit back without consequences. If anything, those who roughed him up the most received his greatest accolade. Those who lacked the courage to join against Wilcox stood on the sidelines and vicariously enjoyed the spectacle. It still felt wonderful to see us kids hitting back, especially from our perch on the sidelines, clean, dry and bruise free. I know well; I was one of them.

While his out-of-place welfare state lecture made no sense, Mr. Wilcox did have one major theme to teach us young impressionable minds, one that was easier to understand. This lecture, often repeated, usually came in soccer practice, soccer being a game of gentlemanly values, and strict rules about fair play. “If you can’t win fair, win by fouling!”, went the refrain. He was dead serious. I wonder how many of us carried this philosophy into our adult lives. I was not one of them. Since I could not even play the game properly, I had no chance at winning, fair or foul. The lecture went through one ear and out the other for me, and my youthful mind never quite caught the dissonant tune Mr. Wilcox carried with his advice as a metaphor for life.

Rugby aside, after several years of terror and abuse a few upper class boys began expressing open rebellion against Mr. Wilcox and getting into fights and scuffles with him. Eventually a major fight erupted between one such boy and Wilcox, an honest to goodness combination of boxing and wrestling in the dusty schoolyard in Nishantash, except that there was no sports purpose to this occasion. It was a vicious display of raw uncontrolled anger in the part of both. Every student in that school claimed to have seen part of this apocalyptic fight. I think one of the older, lofty Turkish teachers broke it up; it may have been Mr. DeLeon. This boy was a bit roughed up during the fight. His parents complained to the school administration. I suppose in retrospect, there must have been many parents who complained. After all, these were the elite and wealthy of Istanbul sending their precious children to this high priced institution for a first class Western education. Physical abuse of their children above and beyond the day’s norm was not within their aspirations. Soon after this fight, we returned to school from a break (Christmas, Easter, I no longer recall) and discovered, to our surprise that Mr. and Mrs. Wilcox were gone. And thus came an abrupt ending to the most colorful teacher in our history.

We eagerly awaited Mr. Wilcox’s replacement, ordered from England, wildly curious as to what he would be like. He turned out to be a mild mannered, Jazz loving, younger man with a properly athletic physique, and a self-effacing manner. His name was Mr. Davies, and we all liked him. Rugby disappeared overnight. So did the fears and tears of P.E. Still, I had a unique experience with Mr. Davies. I sat behind him in the bus one day, on the way over to the field in the edge of the city. He sat alone, I with two other boys in the seat behind him. I must have been pretty loud, rowdy and obnoxious on that ride. Boys tended to be that way and not know it, especially in bus rides. Suddenly and unexpectedly he turned around and slapped me in the face, screaming “SHUT UP!”. I was stunned and stung by this rare and uncharacteristic gesture from Mr. Davies. But it did not hurt. It didn’t come from Mr. Wilcox.

Moris

You made me smile and shiver with old fears at the same time.

thanks